Assets

+ New Loan

£100,000

Liabilities

+ New Deposit

£100,000

A Briefing for Policymakers and Parliamentarians

Based on Bank of England (2014) and Berkeley et al. (2024)

Bank deposits vs central bank money

How banks create money through lending

The UK's institutional architecture

The Consolidated Fund mechanism

What they actually do

The accounting identity that connects all sectors

Real vs perceived constraints

Duration

40 min

Presentation followed by Q&A. Technical appendix with detailed accounting tables available.

Part One

Bank of England, December 2013

When we talk about "money" in the economy, we're overwhelmingly talking about numbers in bank accounts — not physical cash.

The composition of UK broad money:

Bank deposits (commercial bank money): 97%

Currency (notes and coins): 3%

This means understanding money creation requires understanding how these bank deposits come into existence.

Source: Bank of England (2014) "Money creation in the modern economy", Quarterly Bulletin Q1

Fact: 97% of the money we hold is commercial bank deposits.

But this is a stock measure — it tells us what type of money people hold today, not how that money came into existence.

Commercial Bank Lending

When banks make loans, they create matching deposits. This is a major source of money during economic expansions.

Government Spending

Every payment from HM Treasury increases deposits in the commercial banking system. Government deficits are therefore a second source of money creation.

No chart is shown here because neither the Bank of England, ONS, nor HM Treasury publish a dataset that splits money creation between commercial lending and government spending. Monetary statistics record bank lending as increases in broad money, while government spending is recorded as expenditure rather than “money creation,” even though it injects deposits and reserves into the system. As a result, there is no official, directly comparable series for the two flows.

Money issued by the Bank of England

Includes:

• Physical currency (notes & coins)

• Reserves (bank accounts at BoE)

Who holds it: Banks hold reserves; public holds currency

Money created by commercial banks

Includes:

• Current account balances

• Savings account balances

Who holds it: Households, businesses, non-bank financial institutions

Ultimate Authority

Parliament

Power to tax • Consolidated Fund

Monetary Authority

Bank of England

Issues reserves & currency • Settles between banks

Money Creators

Commercial Banks

Create deposits through lending • Hold accounts at BoE

Money Users

Households, Businesses, Non-Bank Financial Institutions

Hold bank deposits • Use money for transactions

Each layer's money is an IOU convertible into money from the layer above.

Adapted from Bell (2001) "The Role of the State and the Hierarchy of Money"

Part Two

"Banks collect deposits from savers and then lend those funds to borrowers..."

🏠

Savers

🏦

Bank

(intermediary)

👤

Borrowers

— Bank of England, Quarterly Bulletin 2014 Q1

Saving does not increase the deposits or 'funds available' for banks to lend.

When a bank makes a loan, it simultaneously creates a matching deposit:

Assets

+ New Loan

£100,000

Liabilities

+ New Deposit

£100,000

Assets

+ Bank Deposit

£100,000

Liabilities

+ Loan Owed

£100,000

This is sometimes called "fountain pen money" — created at the stroke of a banker's pen.

"The central bank controls the money supply by setting the quantity of reserves, which banks then 'multiply up'..."

Central Bank

£100

reserves

Multiplier

10x

(if 10% reserve ratio)

Money Supply

£1,000

deposits

Reserves don't constrain lending

Banks decide how much to lend based on profitable opportunities. They obtain reserves afterwards.

No binding reserve requirements

The UK has no reserve ratio requirement. The BoE supplies reserves on demand to meet settlement needs.

Central banks set interest rates, not the quantity of money. Reserves follow lending, not the other way around.

Banks can't create unlimited money. Three sets of constraints limit money creation:

• Profitability in competitive market

• Capital constraints and risk assessment

• Liquidity and funding management after lending (not a prerequisite to lend)

• Willingness to borrow

• Loan repayments destroy money

• "Reflux" of unwanted money

• Interest rates affect loan demand

• Prudential regulation (capital, liquidity)

• Ultimate constraint

Source: Bank of England (2014) — see also Farag, Harland and Nixon (2013) on capital and liquidity requirements

"Most of the money in circulation is created, not by the printing presses of the Bank of England, but by the commercial banks themselves."

— Bank of England (2014)But what about government spending? How does the state create and inject money into the economy?

Part Three

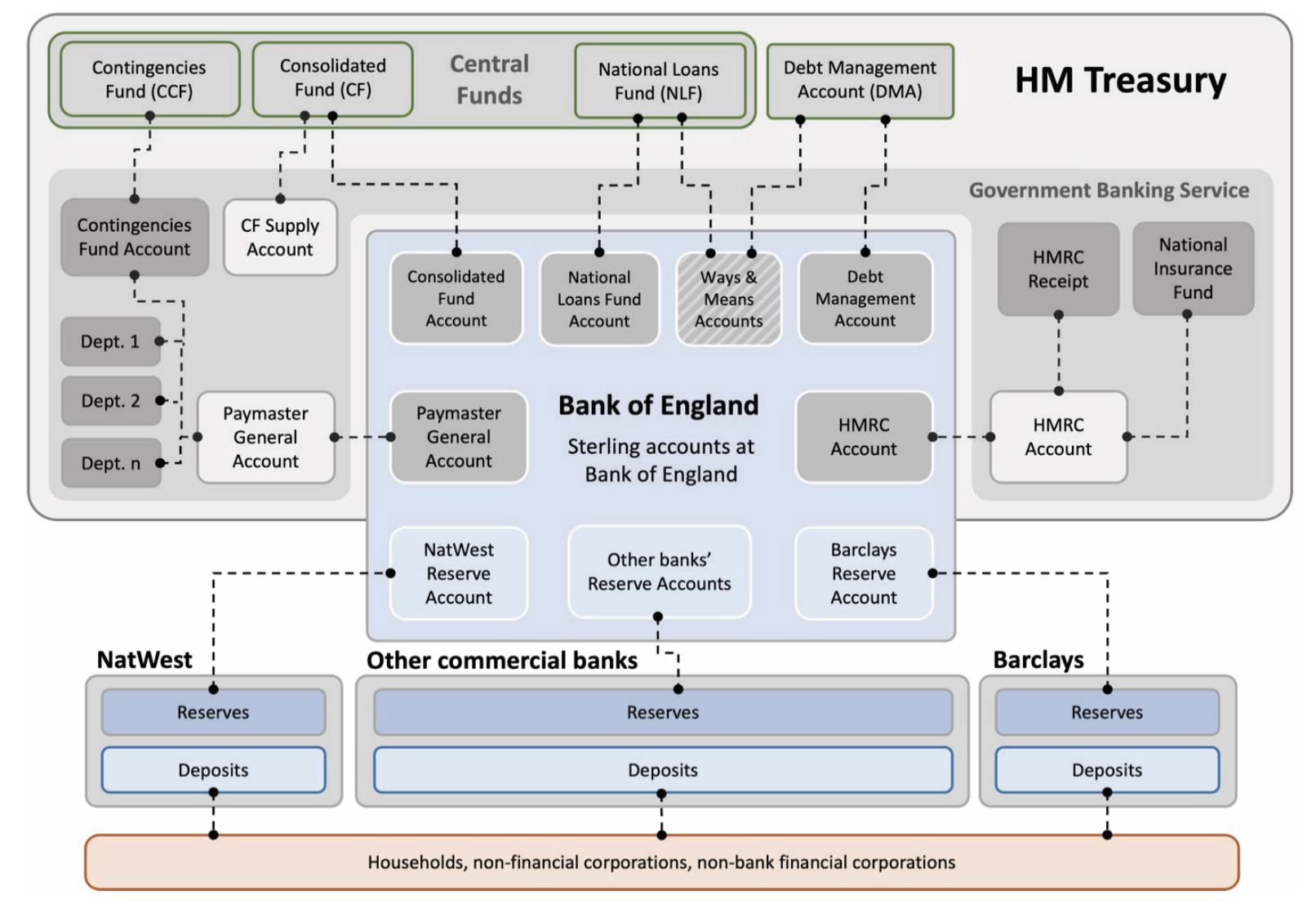

The UK's institutional architecture

The core legal and accounting structure at the heart of UK public finance

Established 1787

"One fund into which shall flow every stream of public revenue, and from which shall come the supply for every service"

— HM Treasury (2024)

What it does:

• Origin of all departmental expenditures

• Source of government securities issuance

• Destination for most government revenue

The Central Funds

Consolidated Fund

“Current account”

National Loans Fund

Lending & borrowing

Contingencies Fund

Urgent expenditure

Governed by Exchequer and Audit Departments Act 1866, National Loans Act 1968

Source: Berkeley et al. (2025), Figure 1

Exchequer and Audit Departments Act 1866, Section 11

"This enactment shall not be construed to empower the Treasury or any authority to direct the payment... of expenditure not sanctioned by any Act whereby services are or may be charged on the Consolidated Fund, or by a vote of the House of Commons..."

Permanently authorized under specific Acts of Parliament

Examples:

• Debt interest payments

• Financial stability interventions

• Contingency advances

Voted annually via Supply and Appropriation Acts

Examples:

• NHS funding

• Education spending

• Defence budget

Two Supply and Appropriation Acts typically passed each year (July and March)

Source: Berkeley et al. (2025)

The Consolidated Fund account at the Bank of England starts every day with a zero balance, yet orders for issues are nevertheless made and fulfilled.

Finance Act 1954, Section 34(3)

"Any sum charged by any Act, whenever passed, on the Consolidated Fund shall be charged also on the growing produce of the Fund"

This connects current spending to "all the revenues to be received in the future" — framing expenditure as credit advanced on the security of future tax revenues.

What This Means

All spending arises as new money advanced as credit, not from taxation or borrowing.

No "Intertemporal Budget Constraint"

There is no ex-ante limit on current or future spending from the accounting mechanics.

See Brittain (1959) "The British Budgetary System" for historical context

Part Four

What they actually do

Exchequer and Audit Departments Act 1866, Section 10

"All public moneys payable to the Exchequer shall be paid into the Consolidated Fund"

Taxpayer

–£100

bank deposit

Commercial Bank

–£100

reserves

HMRC → BoE

+£100

HMRC account

Consolidated Fund

+£100

credits CF

Taxes destroy money

Taxation credits the CF account, offsetting past monetary injections from spending. Money leaves the private sector.

Settled in BoE money

Taxes are finally settled using Bank of England money (reserves), not commercial bank deposits.

The "Full Funding Rule"

"An overarching requirement of debt management policy is that the government fully finances its projected financing requirement each year through the sale of debt."

— DMO Annual Report 2023

Historical Purpose (pre-2009)

Under the "corridor" system, debt issuance drained excess reserves to maintain the target interest rate.

• Net spending adds reserves

• Bond sales drain reserves

• Keeps interbank rate on target

Current Purpose (post-QE)

Under the "floor" system with excess reserves, debt issuance primarily serves different functions:

• Provides safe store of value

• Supplies secure collateral for repo markets

• Supports financial sector liquidity needs

Since 2006, the BoE pays interest on reserves, making the quantity of reserves less relevant for interest rate control.

Part Five

The accounting identity that connects all sectors

Government Balance + Private Sector Balance + Foreign Balance = 0

Sectoral balances are an accounting identity derived from national accounts. Every pound spent by one sector is received by another — the flows must balance.

Government Sector

Deficit = spending > taxation

Surplus = taxation > spending

Private Sector

Surplus = saving > investment

Deficit = investment > saving

Foreign Sector

Surplus = imports > exports (from UK perspective)

Deficit = exports > imports

Based on Godley, W. (1999) "Seven Unsustainable Processes" and national accounting identities (GDP = C + I + G + NX)

Use ↓ to see other countries

Large government deficits matched by large private surpluses

Government deficits fund both private surpluses and current account deficits

Export surpluses allow lower government deficits

Constrained by Eurozone fiscal rules?

The "Balanced Budget" Problem

If the government balances its budget and the country runs a trade deficit, the private sector must go into deficit (spend more than income).

This is unsustainable — private debt accumulates until a crisis forces correction.

Historical Pattern

Every major financial crisis has been preceded by a period of insufficient private sector surpluses or deficits.

Government Deficits Enable Private Saving

For the private sector to net save (accumulate financial assets), the government must run a deficit of equal size (adjusted for trade). This is completely normal, the UK has run deficits for 95% of the time since WWII.

Policy Implication

Arbitrary deficit targets ignore sectoral balance realities. The "appropriate" deficit depends on private sector saving desires and the trade balance — not a fixed percentage of GDP.

See Godley's analysis of the "Goldilocks economy" in the late 1990s predicting the 2001 recession and housing bubble

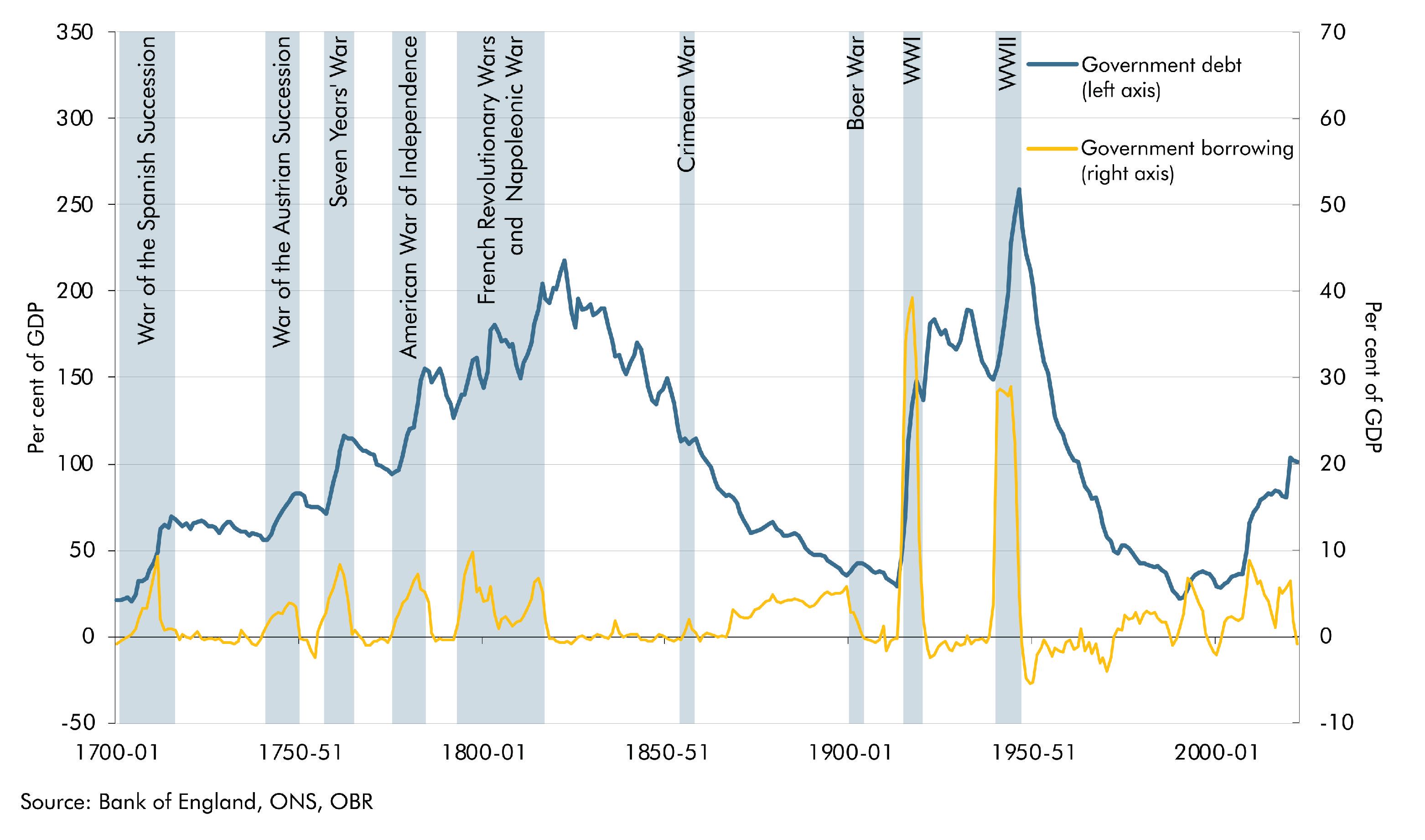

Wars historically drove debt accumulation; peacetime growth and inflation reduced debt ratios

Part Six

Real constraints vs perceived constraints

Constraints That Are NOT Valid

Liquidity Risk

No circumstance where government has "insufficient money" for expenditure requirements

Market Risk / Bond Vigilantes

Banks purchase securities to exchange excess reserves for higher-yielding assets. DMO faces a "seller's market"

Default Risk

Debt payments are Standing Services — permanently authorized by Parliament. Default requires explicit repeal

The REAL Constraints

Inflation

Spending where resources are scarce can create inflationary pressure

Resource Availability

Physical resources, labour, materials are the true limits — not accounting entries

Political/Democratic Choice

Parliament decides priorities. Fiscal rules are policy choices, not operational necessities

"The Government's banking arrangements... ensure that all expenditure authorized by Parliament can be settled."

— HM Treasury, FOI response 2020

The Bank of England is never independent in the sense that it can refuse to facilitate public expenditure.

Legal Obligation

Under the 1866 Act, the BoE has no discretion over whether to extend credit to the Consolidated Fund. This was not changed by the Bank of England Act 1998.

System Dependence

The BoE's assets are almost entirely government securities or loans collateralized by them. HM Treasury provides capital, indemnities, and deposit insurance backing.

What "Independence" Actually Means

Operational independence for monetary policy (setting interest rates) — not independence from facilitating Parliamentary-authorized spending.

The Hierarchy

Parliament's power to tax provides supreme creditworthiness. The BoE is a wholly owned subsidiary of HM Treasury, subject to its direction.

See Financial Services and Markets Act 2000; Banking Act 2009 for Treasury backstop powers

Labour Party Manifesto, 1945

What will the Labour Party do?

First, the whole of the national resources, in land, material and labour must be fully employed. Production must be raised to the highest level and related to purchasing power. Over-production is not the cause of depression and unemployment; it is under-consumption that is responsible.

It is doubtful whether we have ever, except in war, used the whole of our productive capacity. This must be corrected because, upon our ability to produce and organise a fair and generous distribution of the product, the standard of living of our people depends.

Secondly, a high and constant purchasing power can be maintained through good wages, social services and insurance, and taxation which bears less heavily on the lower income groups. But everybody knows that money and savings lose their value if prices rise, so rents and the prices of the necessities of life will be controlled.

Thirdly, planned investment in essential industries and on houses, schools, hospitals and civic centres will occupy a large field of capital expenditure. A National Investment Board will determine social priorities and promote better timing in private investment.

— Labour Party, Let Us Face the Future (1945)

Primary Sources

Bank of England (2014)

"Money creation in the modern economy"

Quarterly Bulletin Q1 2014

Berkeley, A. et al. (2025)

"The Self-Financing State: An Institutional Analysis of Government Expenditure, Revenue Collection and Debt Issuance Operations in the United Kingdom"

Journal of Economic Issues, 59(3), 852-880

Key Legislation

• Exchequer and Audit Departments Act 1866

• Finance Act 1954, Section 34(3)

• National Loans Act 1968

• Bank of England Act 1998

Further Reading

Godley, W. (1999) "Seven Unsustainable Processes" Strategic Analysis, Levy Economics Institute

Godley, W. & Lavoie, M. (2007) Monetary Economics: An Integrated Approach to Credit, Money, Income, Production and Wealth, Palgrave Macmillan

Bell, S. (2000) "Do Taxes and Bonds Finance Government Spending?" Journal of Economic Issues

Tymoigne, E. (2014) "Modern Money Theory, and Interrelations Between the Treasury and Central Bank" Journal of Economic Issues

Fullwiler, S. (2020) "When the Interest Rate on the National Debt Is a Policy Variable" Public Budgeting & Finance

Wray, L.R. (1998) Understanding Modern Money, Edward Elgar

Official Sources

• DMO Annual Reviews

• HM Treasury Consolidated Fund Accounts

• Bank of England Sterling Monetary Framework

Technical appendix with detailed accounting tables

available upon request